Sunday, June 08, 2008

Sunday, June 10, 2007

Monday, December 25, 2006

Friday, August 25, 2006

Tracing His Roots As A Fan

By Bob Ryan, Globe Columnist | August 25, 2006

I appeared to strike a chord in the readership earlier this week by writing the following: ``The truth is we need to sit down and figure what sports are all about. We've lost our way."

It was in reference to the Yankees' infamous five-game sweep of the Red Sox, and the need of many, as I saw it, to find someone to blame for all this, rather than to accept it as a pure athletic situation in which one team simply performed better than another over a period, in this case four days. As always, there are plenty of people who are quite unhappy with the manager, but at present people are displeased in much greater numbers with general manager Theo Epstein, who, in their view, either allowed to get away, traded away, or traded for the wrong people in the last two offseasons and who then angered them further by not putting the Mercurochrome bunny on all this by making a cure-all trade at the July 31 deadline.

Scrutiny of a general manager is not new, but the interpretation of his action or inaction, as the case may be, is now different. Theo has brought some of the criticism on himself because -- he can't be oblivious to this -- the events of last offseason were without precedent in the history of American sport. (I'm trying with great difficulty to picture Branch Rickey, Red Auerbach, or Dick O'Connell in a gorilla suit.) But the rest of it is management's (i.e. Larry Lucchino's) fault for botching the contract negotiations, which, you can be 100 percent certain, Epstein never wanted to be even remotely public.

My God, I'm doing it, aren't I? I'm assigning ``blame." Anyway, the result of all that foolishness was that Theo emerged in the public view as an irreplaceable entity in the Red Sox scheme of things. If he's that smart, people reasoned, then surely he will do all the right things to ensure that we conquer the Evil Empire.

Obviously, he didn't. And now people are e-mailing to say that he is, among other things, cocky, arrogant, delusionary, egotistical, and overrated. And they are not merely disappointed. They are angry. How dare he spoil their summah!

In other words, it's personal. And I am here to say that it didn't used to be personal. It just was.

OK, let's talk fandom.

I know about being a fan. I fell in love with the 1954 New York Giants (especially Willie Mays), and I rooted for them even after they left for San Francisco. I got a Giants jacket as a confirmation gift. I tossed a shoe out of the dormitory window when I heard they had traded Orlando Cepeda to the Cardinals. Juan Marichal is my all-time favorite pitcher (I used to be able to recite his year-by-year record, starting with his 21-8 for Michigan City, Ind., in 1958, but I can no longer do so). When I heard Willie McCovey line out to Bobby Richardson in Game 7 of the '62 Series, I was crushed. But those days are gone. How could anyone root for a team with You Know Who on it? I still have a Giants wastebasket in my home office, but who thinks about replacing wastebaskets?

I rooted for Boston College. I only missed four basketball games (out of 51), home or away, during my junior and senior years. Somehow, someway, I usually figured out a way to get there. I exulted in the wins and took some of the losses quite hard.

I rooted for the 1967 Red Sox. That remains the greatest day-to-day fan experience of my life. I saw a city that had become extremely complacent about the team and the sport come alive thanks to the unexpected rise of a team that had finished ninth the year before and that had not truly contended since 1950, and I was thrilled to participate in the experience. If you're under 50, you must accept it on good faith when I tell you that as you drove around, or went from neighborhood to neighborhood on foot in those days when not all the games were televised, you could keep track of a game's progress by the sound of Ken Coleman and Ned Martin's voices, because everyone was tuned to WHDH (850). That's just what you did. Oct. 1, 1967, was one of the great highlights of a lifetime spent following sports. For me, it will always rank right up there with anything that happened in October 2004.

I still root. I can't help it. It's just me.

I know that many writers wear their professional indifference as a badge of honor, but I don't understand how anyone covering a team wouldn't prefer to see it win, if only because winning people are more likely to be happy people or, at least, accessible people. Winning is in a writer's best interest. There are exceptions, sure. The 2001 Red Sox were a miserable lot. They couldn't lose often enough or fast enough to suit me as that season wore on.

I don't understand not rooting. Any time I go to a neutral college basketball game, for example, it doesn't take long for me to line up with one side or the other, usually because there is a player who intrigues me. It enhances my experience to manufacture a little care about the outcome.

To me, being a fan is understanding the ultimate reality that there are winners and losers and you can't overreact when the team you happen to be backing loses. But even before you go there, being a fan means you actually like the game they're playing and appreciate it for its own sake. Sometimes it's not strictly about wanting your team to win.

Exhibit A would be the night in 2001 when David Cone hooked up with Mike Mussina. For eight innings, the story was this absolutely exhilarating duel between a fine pitcher in the prime of life pitching a superb game (Mussina) and a cagey veteran conjuring up one last flashback effort (Cone). But with the Yankees leading, 1-0, and Mussina having retired the first 26 men he had faced, it became a matter of seeing some history. No true baseball fan wanted to see Carl Everett (ugh) get a hit. A Red Sox victory would have meant nothing in the big scheme of things as opposed to seeing a perfect game. To me, it must start with, and always be about, the baseball, not the blind loyalty to a team. That, I guess, is where I part company with many contemporary Red Sox followers. If that Mussina-Cone matchup had been the seventh game of a playoff series, no, of course not. In that context, you've got to root for the win.

It's a different climate now than it was in 1967. People just inherently knew how to be fans. Red Sox folklore had to do with 1946 (Pesky) and 1948 (Galehouse), but it was pretty benign stuff. No one was taking any of it personally, and that's the big difference.

Blame it on talk radio. Blame it on websites and chat rooms and blogs. Blame it on Shaughnessy (he can take it). But somewhere along the way, far too many members of this so-called ``Red Sox Nation" have perverted the concept of fandom. As a result, there is no more narcissistic group of people rooting for any sports team in North America than that subsection of Red Sox followers who have made the shifting fortunes of the team all about them. When the ball went through Buckner's legs, it was, ``How can he do that to me?" And so it continues.

But don't listen to me. Listen to an e-mailer by the name of Lois Kane. She was introduced to baseball and the Red Sox by her grandfather, who listened to all the games on a portable radio and who, she says, taught her that the idea was ``companionship and enjoyment of the journey through the game." She thinks he would be shocked by ``the attitude that winning was the only important thing."

Concluded Lois, ``In many ways it was more enjoyable to be a fan before it was fashionable to be one."

Thank you, Lois. That's what I'm talking about.

Bob Ryan is a Globe columnist. His e-mail address is ryan@globe.com.

Tracing His Roots As A Fan

By Bob Ryan, Globe Columnist | August 25, 2006

I appeared to strike a chord in the readership earlier this week by writing the following: ``The truth is we need to sit down and figure what sports are all about. We've lost our way."

It was in reference to the Yankees' infamous five-game sweep of the Red Sox, and the need of many, as I saw it, to find someone to blame for all this, rather than to accept it as a pure athletic situation in which one team simply performed better than another over a period, in this case four days. As always, there are plenty of people who are quite unhappy with the manager, but at present people are displeased in much greater numbers with general manager Theo Epstein, who, in their view, either allowed to get away, traded away, or traded for the wrong people in the last two offseasons and who then angered them further by not putting the Mercurochrome bunny on all this by making a cure-all trade at the July 31 deadline.

Scrutiny of a general manager is not new, but the interpretation of his action or inaction, as the case may be, is now different. Theo has brought some of the criticism on himself because -- he can't be oblivious to this -- the events of last offseason were without precedent in the history of American sport. (I'm trying with great difficulty to picture Branch Rickey, Red Auerbach, or Dick O'Connell in a gorilla suit.) But the rest of it is management's (i.e. Larry Lucchino's) fault for botching the contract negotiations, which, you can be 100 percent certain, Epstein never wanted to be even remotely public.

My God, I'm doing it, aren't I? I'm assigning ``blame." Anyway, the result of all that foolishness was that Theo emerged in the public view as an irreplaceable entity in the Red Sox scheme of things. If he's that smart, people reasoned, then surely he will do all the right things to ensure that we conquer the Evil Empire.

Obviously, he didn't. And now people are e-mailing to say that he is, among other things, cocky, arrogant, delusionary, egotistical, and overrated. And they are not merely disappointed. They are angry. How dare he spoil their summah!

In other words, it's personal. And I am here to say that it didn't used to be personal. It just was.

OK, let's talk fandom.

I know about being a fan. I fell in love with the 1954 New York Giants (especially Willie Mays), and I rooted for them even after they left for San Francisco. I got a Giants jacket as a confirmation gift. I tossed a shoe out of the dormitory window when I heard they had traded Orlando Cepeda to the Cardinals. Juan Marichal is my all-time favorite pitcher (I used to be able to recite his year-by-year record, starting with his 21-8 for Michigan City, Ind., in 1958, but I can no longer do so). When I heard Willie McCovey line out to Bobby Richardson in Game 7 of the '62 Series, I was crushed. But those days are gone. How could anyone root for a team with You Know Who on it? I still have a Giants wastebasket in my home office, but who thinks about replacing wastebaskets?

I rooted for Boston College. I only missed four basketball games (out of 51), home or away, during my junior and senior years. Somehow, someway, I usually figured out a way to get there. I exulted in the wins and took some of the losses quite hard.

I rooted for the 1967 Red Sox. That remains the greatest day-to-day fan experience of my life. I saw a city that had become extremely complacent about the team and the sport come alive thanks to the unexpected rise of a team that had finished ninth the year before and that had not truly contended since 1950, and I was thrilled to participate in the experience. If you're under 50, you must accept it on good faith when I tell you that as you drove around, or went from neighborhood to neighborhood on foot in those days when not all the games were televised, you could keep track of a game's progress by the sound of Ken Coleman and Ned Martin's voices, because everyone was tuned to WHDH (850). That's just what you did. Oct. 1, 1967, was one of the great highlights of a lifetime spent following sports. For me, it will always rank right up there with anything that happened in October 2004.

I still root. I can't help it. It's just me.

I know that many writers wear their professional indifference as a badge of honor, but I don't understand how anyone covering a team wouldn't prefer to see it win, if only because winning people are more likely to be happy people or, at least, accessible people. Winning is in a writer's best interest. There are exceptions, sure. The 2001 Red Sox were a miserable lot. They couldn't lose often enough or fast enough to suit me as that season wore on.

I don't understand not rooting. Any time I go to a neutral college basketball game, for example, it doesn't take long for me to line up with one side or the other, usually because there is a player who intrigues me. It enhances my experience to manufacture a little care about the outcome.

To me, being a fan is understanding the ultimate reality that there are winners and losers and you can't overreact when the team you happen to be backing loses. But even before you go there, being a fan means you actually like the game they're playing and appreciate it for its own sake. Sometimes it's not strictly about wanting your team to win.

Exhibit A would be the night in 2001 when David Cone hooked up with Mike Mussina. For eight innings, the story was this absolutely exhilarating duel between a fine pitcher in the prime of life pitching a superb game (Mussina) and a cagey veteran conjuring up one last flashback effort (Cone). But with the Yankees leading, 1-0, and Mussina having retired the first 26 men he had faced, it became a matter of seeing some history. No true baseball fan wanted to see Carl Everett (ugh) get a hit. A Red Sox victory would have meant nothing in the big scheme of things as opposed to seeing a perfect game. To me, it must start with, and always be about, the baseball, not the blind loyalty to a team. That, I guess, is where I part company with many contemporary Red Sox followers. If that Mussina-Cone matchup had been the seventh game of a playoff series, no, of course not. In that context, you've got to root for the win.

It's a different climate now than it was in 1967. People just inherently knew how to be fans. Red Sox folklore had to do with 1946 (Pesky) and 1948 (Galehouse), but it was pretty benign stuff. No one was taking any of it personally, and that's the big difference.

Blame it on talk radio. Blame it on websites and chat rooms and blogs. Blame it on Shaughnessy (he can take it). But somewhere along the way, far too many members of this so-called ``Red Sox Nation" have perverted the concept of fandom. As a result, there is no more narcissistic group of people rooting for any sports team in North America than that subsection of Red Sox followers who have made the shifting fortunes of the team all about them. When the ball went through Buckner's legs, it was, ``How can he do that to me?" And so it continues.

But don't listen to me. Listen to an e-mailer by the name of Lois Kane. She was introduced to baseball and the Red Sox by her grandfather, who listened to all the games on a portable radio and who, she says, taught her that the idea was ``companionship and enjoyment of the journey through the game." She thinks he would be shocked by ``the attitude that winning was the only important thing."

Concluded Lois, ``In many ways it was more enjoyable to be a fan before it was fashionable to be one."

Thank you, Lois. That's what I'm talking about.

Bob Ryan is a Globe columnist. His e-mail address is ryan@globe.com.

Tracing His Roots As A Fan

By Bob Ryan, Globe Columnist | August 25, 2006

I appeared to strike a chord in the readership earlier this week by writing the following: ``The truth is we need to sit down and figure what sports are all about. We've lost our way."

It was in reference to the Yankees' infamous five-game sweep of the Red Sox, and the need of many, as I saw it, to find someone to blame for all this, rather than to accept it as a pure athletic situation in which one team simply performed better than another over a period, in this case four days. As always, there are plenty of people who are quite unhappy with the manager, but at present people are displeased in much greater numbers with general manager Theo Epstein, who, in their view, either allowed to get away, traded away, or traded for the wrong people in the last two offseasons and who then angered them further by not putting the Mercurochrome bunny on all this by making a cure-all trade at the July 31 deadline.

Scrutiny of a general manager is not new, but the interpretation of his action or inaction, as the case may be, is now different. Theo has brought some of the criticism on himself because -- he can't be oblivious to this -- the events of last offseason were without precedent in the history of American sport. (I'm trying with great difficulty to picture Branch Rickey, Red Auerbach, or Dick O'Connell in a gorilla suit.) But the rest of it is management's (i.e. Larry Lucchino's) fault for botching the contract negotiations, which, you can be 100 percent certain, Epstein never wanted to be even remotely public.

My God, I'm doing it, aren't I? I'm assigning ``blame." Anyway, the result of all that foolishness was that Theo emerged in the public view as an irreplaceable entity in the Red Sox scheme of things. If he's that smart, people reasoned, then surely he will do all the right things to ensure that we conquer the Evil Empire.

Obviously, he didn't. And now people are e-mailing to say that he is, among other things, cocky, arrogant, delusionary, egotistical, and overrated. And they are not merely disappointed. They are angry. How dare he spoil their summah!

In other words, it's personal. And I am here to say that it didn't used to be personal. It just was.

OK, let's talk fandom.

I know about being a fan. I fell in love with the 1954 New York Giants (especially Willie Mays), and I rooted for them even after they left for San Francisco. I got a Giants jacket as a confirmation gift. I tossed a shoe out of the dormitory window when I heard they had traded Orlando Cepeda to the Cardinals. Juan Marichal is my all-time favorite pitcher (I used to be able to recite his year-by-year record, starting with his 21-8 for Michigan City, Ind., in 1958, but I can no longer do so). When I heard Willie McCovey line out to Bobby Richardson in Game 7 of the '62 Series, I was crushed. But those days are gone. How could anyone root for a team with You Know Who on it? I still have a Giants wastebasket in my home office, but who thinks about replacing wastebaskets?

I rooted for Boston College. I only missed four basketball games (out of 51), home or away, during my junior and senior years. Somehow, someway, I usually figured out a way to get there. I exulted in the wins and took some of the losses quite hard.

I rooted for the 1967 Red Sox. That remains the greatest day-to-day fan experience of my life. I saw a city that had become extremely complacent about the team and the sport come alive thanks to the unexpected rise of a team that had finished ninth the year before and that had not truly contended since 1950, and I was thrilled to participate in the experience. If you're under 50, you must accept it on good faith when I tell you that as you drove around, or went from neighborhood to neighborhood on foot in those days when not all the games were televised, you could keep track of a game's progress by the sound of Ken Coleman and Ned Martin's voices, because everyone was tuned to WHDH (850). That's just what you did. Oct. 1, 1967, was one of the great highlights of a lifetime spent following sports. For me, it will always rank right up there with anything that happened in October 2004.

I still root. I can't help it. It's just me.

I know that many writers wear their professional indifference as a badge of honor, but I don't understand how anyone covering a team wouldn't prefer to see it win, if only because winning people are more likely to be happy people or, at least, accessible people. Winning is in a writer's best interest. There are exceptions, sure. The 2001 Red Sox were a miserable lot. They couldn't lose often enough or fast enough to suit me as that season wore on.

I don't understand not rooting. Any time I go to a neutral college basketball game, for example, it doesn't take long for me to line up with one side or the other, usually because there is a player who intrigues me. It enhances my experience to manufacture a little care about the outcome.

To me, being a fan is understanding the ultimate reality that there are winners and losers and you can't overreact when the team you happen to be backing loses. But even before you go there, being a fan means you actually like the game they're playing and appreciate it for its own sake. Sometimes it's not strictly about wanting your team to win.

Exhibit A would be the night in 2001 when David Cone hooked up with Mike Mussina. For eight innings, the story was this absolutely exhilarating duel between a fine pitcher in the prime of life pitching a superb game (Mussina) and a cagey veteran conjuring up one last flashback effort (Cone). But with the Yankees leading, 1-0, and Mussina having retired the first 26 men he had faced, it became a matter of seeing some history. No true baseball fan wanted to see Carl Everett (ugh) get a hit. A Red Sox victory would have meant nothing in the big scheme of things as opposed to seeing a perfect game. To me, it must start with, and always be about, the baseball, not the blind loyalty to a team. That, I guess, is where I part company with many contemporary Red Sox followers. If that Mussina-Cone matchup had been the seventh game of a playoff series, no, of course not. In that context, you've got to root for the win.

It's a different climate now than it was in 1967. People just inherently knew how to be fans. Red Sox folklore had to do with 1946 (Pesky) and 1948 (Galehouse), but it was pretty benign stuff. No one was taking any of it personally, and that's the big difference.

Blame it on talk radio. Blame it on websites and chat rooms and blogs. Blame it on Shaughnessy (he can take it). But somewhere along the way, far too many members of this so-called ``Red Sox Nation" have perverted the concept of fandom. As a result, there is no more narcissistic group of people rooting for any sports team in North America than that subsection of Red Sox followers who have made the shifting fortunes of the team all about them. When the ball went through Buckner's legs, it was, ``How can he do that to me?" And so it continues.

But don't listen to me. Listen to an e-mailer by the name of Lois Kane. She was introduced to baseball and the Red Sox by her grandfather, who listened to all the games on a portable radio and who, she says, taught her that the idea was ``companionship and enjoyment of the journey through the game." She thinks he would be shocked by ``the attitude that winning was the only important thing."

Concluded Lois, ``In many ways it was more enjoyable to be a fan before it was fashionable to be one."

Thank you, Lois. That's what I'm talking about.

Bob Ryan is a Globe columnist. His e-mail address is ryan@globe.com.

Tracing His Roots As A Fan

By Bob Ryan, Globe Columnist | August 25, 2006

I appeared to strike a chord in the readership earlier this week by writing the following: ``The truth is we need to sit down and figure what sports are all about. We've lost our way."

It was in reference to the Yankees' infamous five-game sweep of the Red Sox, and the need of many, as I saw it, to find someone to blame for all this, rather than to accept it as a pure athletic situation in which one team simply performed better than another over a period, in this case four days. As always, there are plenty of people who are quite unhappy with the manager, but at present people are displeased in much greater numbers with general manager Theo Epstein, who, in their view, either allowed to get away, traded away, or traded for the wrong people in the last two offseasons and who then angered them further by not putting the Mercurochrome bunny on all this by making a cure-all trade at the July 31 deadline.

Scrutiny of a general manager is not new, but the interpretation of his action or inaction, as the case may be, is now different. Theo has brought some of the criticism on himself because -- he can't be oblivious to this -- the events of last offseason were without precedent in the history of American sport. (I'm trying with great difficulty to picture Branch Rickey, Red Auerbach, or Dick O'Connell in a gorilla suit.) But the rest of it is management's (i.e. Larry Lucchino's) fault for botching the contract negotiations, which, you can be 100 percent certain, Epstein never wanted to be even remotely public.

My God, I'm doing it, aren't I? I'm assigning ``blame." Anyway, the result of all that foolishness was that Theo emerged in the public view as an irreplaceable entity in the Red Sox scheme of things. If he's that smart, people reasoned, then surely he will do all the right things to ensure that we conquer the Evil Empire.

Obviously, he didn't. And now people are e-mailing to say that he is, among other things, cocky, arrogant, delusionary, egotistical, and overrated. And they are not merely disappointed. They are angry. How dare he spoil their summah!

In other words, it's personal. And I am here to say that it didn't used to be personal. It just was.

OK, let's talk fandom.

I know about being a fan. I fell in love with the 1954 New York Giants (especially Willie Mays), and I rooted for them even after they left for San Francisco. I got a Giants jacket as a confirmation gift. I tossed a shoe out of the dormitory window when I heard they had traded Orlando Cepeda to the Cardinals. Juan Marichal is my all-time favorite pitcher (I used to be able to recite his year-by-year record, starting with his 21-8 for Michigan City, Ind., in 1958, but I can no longer do so). When I heard Willie McCovey line out to Bobby Richardson in Game 7 of the '62 Series, I was crushed. But those days are gone. How could anyone root for a team with You Know Who on it? I still have a Giants wastebasket in my home office, but who thinks about replacing wastebaskets?

I rooted for Boston College. I only missed four basketball games (out of 51), home or away, during my junior and senior years. Somehow, someway, I usually figured out a way to get there. I exulted in the wins and took some of the losses quite hard.

I rooted for the 1967 Red Sox. That remains the greatest day-to-day fan experience of my life. I saw a city that had become extremely complacent about the team and the sport come alive thanks to the unexpected rise of a team that had finished ninth the year before and that had not truly contended since 1950, and I was thrilled to participate in the experience. If you're under 50, you must accept it on good faith when I tell you that as you drove around, or went from neighborhood to neighborhood on foot in those days when not all the games were televised, you could keep track of a game's progress by the sound of Ken Coleman and Ned Martin's voices, because everyone was tuned to WHDH (850). That's just what you did. Oct. 1, 1967, was one of the great highlights of a lifetime spent following sports. For me, it will always rank right up there with anything that happened in October 2004.

I still root. I can't help it. It's just me.

I know that many writers wear their professional indifference as a badge of honor, but I don't understand how anyone covering a team wouldn't prefer to see it win, if only because winning people are more likely to be happy people or, at least, accessible people. Winning is in a writer's best interest. There are exceptions, sure. The 2001 Red Sox were a miserable lot. They couldn't lose often enough or fast enough to suit me as that season wore on.

I don't understand not rooting. Any time I go to a neutral college basketball game, for example, it doesn't take long for me to line up with one side or the other, usually because there is a player who intrigues me. It enhances my experience to manufacture a little care about the outcome.

To me, being a fan is understanding the ultimate reality that there are winners and losers and you can't overreact when the team you happen to be backing loses. But even before you go there, being a fan means you actually like the game they're playing and appreciate it for its own sake. Sometimes it's not strictly about wanting your team to win.

Exhibit A would be the night in 2001 when David Cone hooked up with Mike Mussina. For eight innings, the story was this absolutely exhilarating duel between a fine pitcher in the prime of life pitching a superb game (Mussina) and a cagey veteran conjuring up one last flashback effort (Cone). But with the Yankees leading, 1-0, and Mussina having retired the first 26 men he had faced, it became a matter of seeing some history. No true baseball fan wanted to see Carl Everett (ugh) get a hit. A Red Sox victory would have meant nothing in the big scheme of things as opposed to seeing a perfect game. To me, it must start with, and always be about, the baseball, not the blind loyalty to a team. That, I guess, is where I part company with many contemporary Red Sox followers. If that Mussina-Cone matchup had been the seventh game of a playoff series, no, of course not. In that context, you've got to root for the win.

It's a different climate now than it was in 1967. People just inherently knew how to be fans. Red Sox folklore had to do with 1946 (Pesky) and 1948 (Galehouse), but it was pretty benign stuff. No one was taking any of it personally, and that's the big difference.

Blame it on talk radio. Blame it on websites and chat rooms and blogs. Blame it on Shaughnessy (he can take it). But somewhere along the way, far too many members of this so-called ``Red Sox Nation" have perverted the concept of fandom. As a result, there is no more narcissistic group of people rooting for any sports team in North America than that subsection of Red Sox followers who have made the shifting fortunes of the team all about them. When the ball went through Buckner's legs, it was, ``How can he do that to me?" And so it continues.

But don't listen to me. Listen to an e-mailer by the name of Lois Kane. She was introduced to baseball and the Red Sox by her grandfather, who listened to all the games on a portable radio and who, she says, taught her that the idea was ``companionship and enjoyment of the journey through the game." She thinks he would be shocked by ``the attitude that winning was the only important thing."

Concluded Lois, ``In many ways it was more enjoyable to be a fan before it was fashionable to be one."

Thank you, Lois. That's what I'm talking about.

Bob Ryan is a Globe columnist. His e-mail address is ryan@globe.com.

Year Three

Following the Sox putrid and horrid collapse against the Yankees last week, (a stunning five-game sweep at Fenway) in which I was present for Game 1 of the debacle, BR came up with this article...

Warning: These truths may hurt

By Bob Ryan, Globe columnist | August 22, 2006

You want the truth?

OK. Let's see if you can handle the truth.

The truth is that at present the Red Sox have two reliable pitchers, Curt Schilling and Jonathan Papelbon.

The truth is that, while you cannot blame everything on not having Jason Varitek, you cannot ignore his loss, either. They are 6-15 in his absence. There is some connection.

The truth is that there has been no legitimate No. 5 hitter on this team all season. It wasn't Varitek and it wasn't Trot Nixon. It most certainly is not Kevin Youkilis. It isn't Mike Lowell. The guy's not quite ready yet, but the closest thing would be Wily Mo Peña, and the truth is that he generally bats right where any decent team currently would put him: seventh.

The truth is that Johnny Damon was an enormous loss for the Red Sox and a tremendous addition to the Yankees. Over and above his obvious offensive skills, he has an irreplaceable personality. People who know the Yankees well say they have never before known such a relaxed Yankee clubhouse, and they attribute it all to the daily presence of Damon. He will not be playing center field when his current Yankee contract expires, but he will be in the lineup somewhere. They consider him money well spent (as only they could).

The truth is that Coco Crisp is not the player the Red Sox thought he was. He was enticing because he appeared to be getting better at the plate with each passing year, and the expectation was that further improvement was a given. Well, it wasn't, and that's not a strange baseball occurrence, especially when someone is changing teams. My guess is that he will be a much more productive player next year, but it's foolish to think he's going to be Johnny Damon. Fans cannot hold him to that standard.

The truth is that Josh Beckett is a mystery. Is he stupid? Is he stubborn? Is he lacking in focus? Is he a National League fraud? I do not know for sure what the answer is, but if someone can't find the solution to his problem, he will represent a monumental miscalculation and a colossal waste of money. His second-half performance has been pathetic.

The truth is that Theo Epstein whiffed on his big bullpen acquisitions. Julian Tavarez and Rudy Seanez were each coming off very good seasons. Tavarez had been a reliable middle guy for several seasons, while Seanez, long one of the great teases in baseball, had posted a career year in San Diego (7-1, 2.69, 84 K's and 22 walks). I don't have to tell you how it's turned out.

The truth is that everyone has to get old sometime and it appears that Mike Timlin's time has come. Some trace it to the World Baseball Classic in the spring. Maybe. I really don't know. I do know that when he gets up in that bullpen now, Red Sox fans get nervous, and with good reason. I also know that it was beyond stupid for a 16-year veteran to throw his offense under the bus as Timlin did early last week. You think a few guys in that clubhouse weren't smirking when he blew the second game last Friday night?

The truth is that if you're going to go through most of the season without a major league lefty in your bullpen, you'd better have a very good reason. You'd better have a righty who is exceptionally tough on lefties, and the only person on the Sox roster who could answer that description was Keith Foulke, and then only when he is at the very peak of his game. I really don't know why the Red Sox allowed Mike Myers to skip town, and I would be saying that even if he hadn't K'd Big Papi with his 80-m.p.h. heater in a key situation yesterday. ``Mike Myers is the consummate pro," said Joe Torre afterward, and I would second that notion.

The truth is that the Red Sox made their big move against the (inferior) National League, and they weren't alone. The Red Sox, Tigers, White Sox, and Twins were a combined 61-11 against the NL. I know that looks ridiculous, but it's the gospel truth. The Red Sox are now officially .500 in their own league. Now we must accept the fact that they were never really that good.

The truth is that this has been a very good year to be a Yankee fan. They lost Gary Sheffield and Hideki Matsui within two weeks in the spring, they also lost the scary-good Robinson Cano for about six weeks, and they had concurrent problems with their starting pitching. They had to wait out a Red Sox surge, knowing there was plenty of time in a long, long season to pull themselves together. In its present form, it is a thoroughly likeable and rootable team.

The truth is that the only team in baseball that could take on the Bobby Abreu contract was the team that did so. And while people knew he was good, no one foresaw him having this much of an effect on the rest of the lineup. A lineup that already had some patient hitters now has become a pitcher's nightmare. Schilling might have gone nine Sunday night if he didn't need 41 pitches to get six outs during the scoreless first and second innings.

The truth is that Brian Cashman's moves in getting Scott Proctor, Ron Villone, and Kyle Farnsworth to form his setup corps are now looking every bit as good as Theo's moves now look bad. You don't see any Craig Hansens or Manny Delcarmens doing their OJT in the middle of a pennant race because the big-money vets have been completely inadequate.

The truth is that Derek Jeter is submitting an MVP season. When the Yankees were going through their problems, the one person they always could count on was Jeter. He is both highly skilled and single-minded in the pursuit of victory. He is the last man any Red Sox fan should ever want to see up in any meaningful situation. There was enough evidence of that in this series.

The truth is that the Yankees lost two very good players in Sheffield and Matsui, but they retained such players as Damon, Jeter, Jason Giambi, Abreu, and Alex Rodriguez, none of whom makes less than $13 million a year. That's before you get to Randy Johnson. See any other teams around like that?

The truth is that, in addition to the big-money guys, the Yankees in the space of a year presented for the perusal of their fans the likes of Chien-Ming Wang, Cano, and Melky Cabrera from their farm system. Give them credit.

The truth is that this is not a good time to be Theo Epstein. For two years running, he has been unable to construct a viable pitching rotation. (We haven't mentioned Matt Clement, a very nice guy; no one is in a hurry to see him come back, because it's clear he wasn't cut out for Boston.) Theo was cut one year of afterglow slack, but overheated fans, already in a bloodthirsty mood, are downright rebellious now that the Yankees have humiliated their team with a five-game sweep.

The truth is that the essential Yankee/Red Sox dynamics haven't changed, no matter what happened in the fall of 2004. The Red Sox have a lot of money, but the Yankees HAVE A LOT OF MONEY. The real story is that the Yankees have not won since 2000. They're winless in this century. People around here should focus more on that. The Yankees have some splainin' to do.

The truth is that in this perverted sports climate, the other team is never just allowed to be better, even for a day, let alone a series or a season. No, no. Blame must be affixed. Heads must be severed.

Once upon a time, losing brought a brief period of sorrow. Now it brings rage. The rest of the season, I fear, will not be much fun.

The truth is we need to sit down and figure out what sports are all about. We've lost our way.

Bob Ryan is a Globe columnist. His e-mail is ryan@globe.com

Sunday, August 20, 2006

Where Do Rivals Draw the Line?

New York Times - August 18, 2006

Where Do Rivals Draw the Line?

By JOHN BRANCH

THE CITY of New Britain, near the geographical center of Connecticut and the midpoint between New York City and Boston, is home to the Rock Cats, the Minnesota Twins’ Class AA affiliate in the Eastern League. But the Twins do not have much of a fan base in New Britain. As is the case across much of the state, there is a debate in New Britain about which is the more popular team, the Red Sox or the Yankees.

Last summer, the Rock Cats staged a Rivalry Night. They had 2,000 Yankees caps and 2,000 Red Sox caps. Paying customers could choose one.

“The Red Sox caps ran out first, so we declared this Red Sox territory, although it’s probably 51-49,” said Bob Dowling, the team’s media relations director.

A city divided. A region and state, too. But where, exactly?

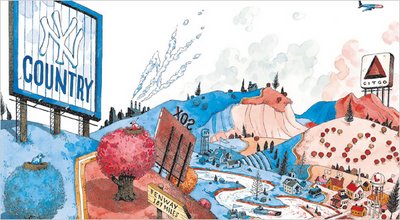

The idea for this exercise was simple in design but complicated in application: Plot the length of the border between Red Sox Nation and Yankees Country, a sort of Mason-Dixon Line separating baseball’s fiercest rivals, who will play five games in the next four days in Boston.

The midpoint between Fenway Park and Yankee Stadium is approximately Rocky Hill, Conn., a few miles south of Hartford and east of New Britain. Some adventurers have dared to guess where allegiances are perfectly balanced, usually pointing to a place near Route 91, anywhere from north of Hartford to New Haven in the south.

But few have set out on an expedition — Lewis and Clark meet Rand McNally — to draw baseball’s bitterest border, to learn where it makes landfall along Long Island Sound to where it peters out in complacency in upstate New York, a serpentine span of nearly 200 miles.

“The border’s probably as wide as Connecticut,” Tom Brown, a volunteer firefighter in Old Lyme, Conn., said.

But the point was to narrow the boundary until each adjacent town fell to one side or the other. The border would be a continuous line, allowing no recognized islands of hostility in enemy territory. Such bastions would be viewed as anomalies, like Union sympathizers in Tennessee. True borders, after all, are no wider than a dotted line.

Polling a representative sample of people in every town would be impossible, so the method was simplified: Use a company-issued 2002 Pontiac Grand Am to traverse the highways and back roads of Connecticut, New York and Massachusetts. Roll into towns unannounced. Choose a person or group of people — preferably those with a bead on the area, like police officers and firefighters, politicians and postal carriers, bartenders and barbers — to be the proxy for their village. Excuse me, but is this a Yankees town or Red Sox one?

When possible, irrefutable data — a choice of baseball caps, for example, or the sale of team-logo cookies, or an office straw poll — would be used for confirmation.

This one is a Red Sox town? That one is for the Yankees? The border goes between. And so on.

That is how it was determined that the divide goes north of Southington but south of Northfield, that New Haven belongs to the Yankees, New London to the Red Sox.

Connecticut Yankees?

The results of a poll by Connecticut’s Quinnipiac University, released in May, served as a loose guide, like a AAA TripTik. Of those in Connecticut who said they were “somewhat interested” or “very interested” in major league baseball, 42 percent of them claimed the Yankees as their favorite team. The Red Sox were preferred by 35 percent. The Mets, at 12 percent, were a distant third.

Fairfield County, the southwestern spout of Connecticut, which spills toward New York City, belongs to the Yankees, 55 percent to 14 percent.

But five of Connecticut’s eight counties, the poll found, are part of Red Sox Nation. That includes Hartford County, which favors the Red Sox by 52 percent to 30 percent. That jibes with television ratings, which show that the Red Sox usually get a larger audience in the area.

The first goal of the expedition was to determine where the border crosses the Connecticut shoreline, hugged by Route 95. A pair of Lids stores, which sell a large variety of caps, revealed that it begins somewhere on the 55-mile stretch between Exit 39B and Exit 82.

At the Connecticut Post Mall in Milford, west of New Haven, a wall near the register was dominated by classic Yankees caps and about 40 variations. Red Sox caps were displayed on the low racks, like bargain cereal in the supermarket aisle.

“It’s supply and demand,” the assistant manager Luis Sanchez said. He wore a Yankees cap. “Obviously, the Yankees hats are doing their thing.”

An hour later, at the Crystal Mall in Waterford, near New London, the Lids store was dominated by Red Sox caps.

It prompted the first of countless U-turns. Focus shifted to the Connecticut River.

“In one word: brackish,” said Joan Welch of the Wheatmarket deli in Chester, applying the term both to the river — near its mouth, a mix of seawater and fresh water — and to the baseball allegiances that it symbolically dissects.

Old Saybrook sits on the west side of the river. The executive director of its chamber of commerce, Linanne Lee, said she thought the town leaned toward the Yankees. The office manager Judy Sullivan, a Yankees fan, said it leaned toward the Red Sox. After much deliberation, it was decided: Line the streets of Old Saybrook with pinstripes, but do it faintly.

Across the river, members of the Old Lyme volunteer fire department, in two engines with lights flashing and sirens blaring, rushed to the Hideaway Restaurant and Pub. A car in the parking lot had a gas leak and could not be towed until it was examined.

Inside the Hideaway, a television showed the Yankees playing an afternoon game. Two others showed a tape of the Red Sox game from the night before. Outside, 10 firefighters stood in the midday sun. Six of them liked the Red Sox, three the Yankees. One, perhaps a Mets fan, abstained.

Cookie-Cutter Answers

The baseball border quickly abandons the river. There is little doubt that everything east of the Connecticut River leans to the Red Sox. But crossing to the west on the Chester-Hadlyme Ferry, the river-as-border theory crumbles like a cookie at Kristen Lynn Bakery in Chester.

The owner Kristen Ehrlich makes cookies shaped like ball caps, frosted with near-perfect logos of the Yankees and the Red Sox.

“I make the Yankees when they run out, but I’m making the Red Sox all the time,” she said. “The Red Sox are definitely the better seller.”

Backtracking again found that the border bends sharply west from the river’s mouth, back along I-95. The Yankees claim most of the beach towns. The Red Sox scoop up many inland villages, which feel quintessentially New England rather than metropolitan New York.

The border swings back to the river at aptly named Middletown. Employees at Bill’s Sport Shop said the city favored the Yankees, thanks to its substantial, but aging, Italian-American population, fans who once rooted for DiMaggio, Berra and Rizzuto.

But Eli Cannon’s, a tavern where regulars keep their mugs hanging behind the bar, was filled largely with Red Sox fans.

Five firefighters and a paramedic watching darkness fall outside the station on Main Street debated the topic — three said Yankees, three said Red Sox — until an alarm sent them scurrying.

Brian O’Connor broke the tie. A state representative and a director of the Middlesex County Chamber of Commerce, he risked alienating his Red Sox constituents and put Middletown on the Yankees side.

North of Middletown, in Cromwell, a woman flipping eggs on the grill at Mama Roux’s Kitchen declared the area Yankees Country. She could tell by the T-shirts worn by customers.

In the next town to the north, Rocky Hill, near the edge of Hartford’s sprawl, employees at the post office said the town was part of Red Sox Nation. More evidence was provided by the post office’s sales of team-logo door magnets: Red Sox 15, Yankees 12.

Rocky Hill is where the border takes a hard turn west, toward New Britain and then Bristol.

Thrown a Curve

Satellite dishes, part of the vast ESPN complex, stand sentry to Bristol’s east side. Chris LaPlaca, ESPN’s senior vice president for communications, placed Bristol on the Red Sox side. Bristol was the home of the Bristol Red Sox, who moved to New Britain and later became the Rock Cats, helping to tinge the area red.

South of Bristol is Southington, where Yankees pitcher Carl Pavano grew up and, with little debate, a Yankees town.

As the border ducks into the hills of western Connecticut, there seemed no better place to break the near-deadlock in Terryville, a border town, than the Lock Museum of America. Alas, on this afternoon, during posted business hours, the museum was closed — and locked.

Reached at home, the museum’s curator, Tom Hennessy, put tiny Terryville in the Red Sox camp with conviction, enough to throw away the key.

From Terryville, the border curves north again and forms a backward “S” across Route 8. In Torrington, a query at the aptly named Yankee Pedlar Inn was deferred to Dick’s Restaurant. In this narrow throwback of a bar, a wall is lined with Yankees memorabilia, including photographs of the restaurant owner, Raymond Colangelo, with famous Yankees, like Mickey Mantle. Colangelo, known as Brooklyn, grew up in Torrington and has been at Dick’s for 43 years. Torrington is a Yankees town, he said.

It is there that tracing the border through the hilly northwest corner of Connecticut becomes tricky, the result of a decrease in population and an increase in apathy. The Quinnipiac poll found 64 percent of Litchfield County residents were “not at all” interested in baseball — a number 20 points higher than any other part of the state.

Still, patrons at the Speckled Hen Pub in Norfolk quickly dubbed the town part of Red Sox Nation. Against the Massachusetts border a few miles northwest, at the Steppin’ Stone, a restaurant in Canaan, it was agreed that that town was part of Yankees Country.

This is the area where the swerves of the baseball boundary harden into straight lines. A Red Sox town in New York is more likely than a Yankees town in Massachusetts, though the state line seems built on baseball as much as colonial politics.

Kristin Keeler was raised in Hillsdale, N.Y., minutes from Massachusetts. From behind the counter at Hillsdale Electronics, she professed her hometown’s allegiance to the Yankees.

A few miles east over the hills, Sheffield, Mass., is closer to New York City than to Boston, but its heart is with the Red Sox.

“It’s 157 miles to Yawkey Way,” said Edward Gulotta, who runs a Mobile gas station with his brother, Tony, referring to the street address of Fenway Park. “We’re pretty loyal to the state.”

Inside, above the candy racks, were framed photographs of the 2004 World Series trophy taken in front of the station when the team took the trophy on a statewide tour. A nearby shelf held disposable lighters decorated with the Yankees logo. There were none with the Red Sox emblem.

“That’s a good test,” Tony Gulotta said. “We had the same number of Red Sox lighters. And these are still here.”

His brother lifted one. “These cost $100, and they don’t work,” he said.

Next door, five people worked inside town hall, and all were Red Sox fans. Only the absent tax collector was a Yankees fan, threatening his popularity on two counts.

A few miles north, in Great Barrington, a police officer, Paul Montgomery, directed traffic around a large hole in the street where workers were repairing a water pipe. Red Sox, he declared without hesitation. And two out of three workers agreed.

Beyond Borders

Still, there are complicated allegiances in the Berkshires region of western Massachusetts, especially during baseball season. Dan Duquette, the former Red Sox general manager, runs a sports academy in Hinsdale, where the population doubles in the summer.

“You get a number of New Yorkers who spend summers here,” Duquette said. “When you get all these transplanted New Yorkers up here, you can almost get more Yankees fans.”

But not quite. WBRK, a Pittsfield radio station, broadcasts Yankees games, and the station’s president, Chip Hodgkins, estimates that there is nearly a 50-50 split in the area’s allegiances. Pressed, he conceded a 60-40 split, advantage to the Red Sox. In the end, the search found no Massachusetts town outside Red Sox Nation.

But a couple of New York towns might fall to the Red Sox side. New Lebanon is about a mile from the state line, a quick jaunt from Pittsfield. Several stops — at the fire station, a coffee shop and a bar — were met with conflicting responses. At the post office, three employees delivered the town’s allegiance to the Red Sox. A customer claimed it for the Yankees, and a teenager in a Yankees cap deemed it too close to call.

A more telling sign was needed. On a house across the street, a Red Sox flag hung from the porch.

Farther north, along the Vermont state line, the crowd at Helvi’s BBQ in Hoosick, N.Y. — where a full pig was baking in a barbecue set on a trailer hitched to a truck, ready to be taken to a party — leaned toward the Red Sox. Nearby Hoosick Falls, however, was firmly in the Yankees camp.

To see if the Yankees had moved deep into New England, a side trip to nearby Bennington, Vt., found it in Red Sox Nation.

“I have to go to Hoosick to watch the games,” said a lone Yankees fan at Carmody’s Irish Pub. He was headed there that night.

The border extends north, surely, and probably a little west, perhaps beyond Lake Champlain and into Canada. But allegiances are dulled by distance, and every mile on the Grand Am — 600 and counting on this expedition — was met with diminishing returns.

Increasingly, there were no exact answers. Only debatable ones. As it should be.

Wednesday, August 02, 2006

10th Avenue Freeze Out!

Tuesday, August 01, 2006

This hit-maker is off the charts

This was Ortiz's third walkoff homer this year, his seventh regular-season walkoff homer with the Red Sox, and the eighth regular-season walkoff homer of his career. He has two postseason walkoff homers. He has 15 regular-season walkoff hits and five walkoff hits in the last 51 days. He has 37 homers and 105 RBIs after 104 games. He hit 14 homers in July with 35 RBIs. He is the American League MVP at this hour.